AS the annual bull selling season approaches, it can be possible to detect an undercurrent of excitement shared among commercial cattle and seedstock producers.

Much of this excitement is driven from the opportunities associated with observing new sires that seedstock breeders are offering, as well as the anticipation of making a degree of change and progress within a herd.

While this is an exciting period, it is worth remembering that genetic improvement in a herd doesn’t rest entirely on finding new sires.

This can often be a challenge in the selling season. It is not uncommon to overhear producers commenting on the overwhelming amount of information and promotion coming from seedstock breeders, highlighting the next ‘stud.’

As a result, along with the excitement of finding that new ‘stud’ there is a lot of pressure associated with this aspect of selection. This pressure comes from not only identifying potential sires to consider, but then to understand their genetic merit, price and even the ability to physically inspect and then potentially bid on a choice.

Given all the focus on finding the ‘studs’, it’s not unsurprising that producers often forget that genetic improvement can also be achieved by identifying the ‘duds’ in a herd. Genetic progress is achieved not only by the introduction of new animals with higher genetic merit – it also requires a degree of intensity in the selection of breeding females.

Selection intensity may not always create the degree of excitement associated with looking for new sires. However, it is an undertaking that most herds undertaken on a reasonably regular basis.

Much of this selection in the breeding herd occurs on the basis of obvious production factors. These include pregnancy status; age; physical injuries or deterioration and temperament.

Just how hard producers look at individual animals and remove those that fall short of an acceptable production level determines the intensity of selection. In general, most producers maintain a reasonably constant level of intensity, varying only when seasonal factors, or perhaps rebuilding or expanding herd numbers forces a change.

The result of this constant level of intensity defaults much genetic progress back onto selection of sires. Placing greater pressure on identifying the ‘studs’ and avoiding the ‘duds’.

This default setting, based largely on removing the most obvious ‘duds’ from a herd often restricts the rate of genetic improvement. It can also be argued that this strategy, while keeping a herd largely stable, does mean that the full benefit of investing in superior genetics is never realised to the full extent.

In other words, to make the investment in a new ‘stud’, it’s important not to waste that opportunity on the ‘duds’ in the breeding herd.

Beyond the more obvious factors identified earlier, there are always other methods producers can include. Much of this does require more effective and targeted data collection.

Useful measures

The long running Cash Cow project in Northern Australia highlighted the value of collecting data and analysing it on the basis of liveweight production.

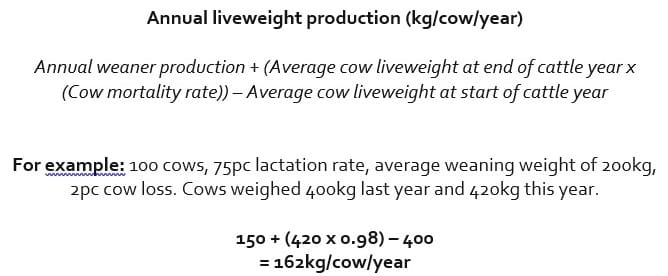

One useful measure that can be used in any breeding program is to actually record and analyse annual liveweight production per cow. While many producers choose to measure and record data associated with weaning rate, annual production per cow actually encapsulates the important factors of body weight change and in extensive regions the impact of mortality and missing breeders.

Although this is a metric developed from a program focussed on northern production, it is one that can be used in any breeding program as a way to start sorting out the ‘duds’.

This calculation can be undertaken annually and can be used to rank cattle from the most to the least productive. This adds a degree of rigour and selection intensity that is focussed on drivers of productivity within a breeding herd.

By ranking cattle in this way, it becomes very clear which animals in the herd can be considered as, if not a dud, as an animal that is restricting progress.

Source: Cash Cow Summary – MLA

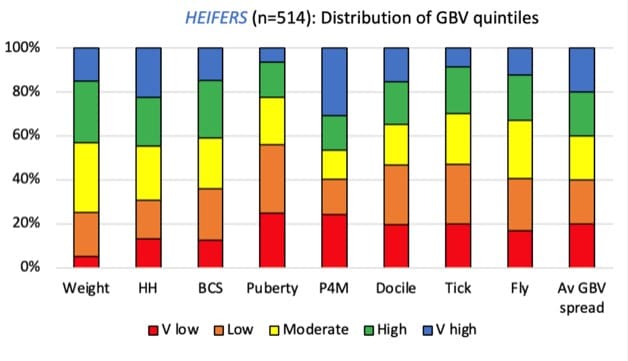

The development of genomic technologies, particularly the recent release of Genomic Breeding Values (GBVs) increases the opportunity to identify the genetic potential of a herd beyond analysing annual liveweight production in northern herds.

In northern herds, producers can now rank their breeders on the basis of genetic merit for specific traits that impact on the productivity and profitability of an enterprise.

Combining genetic evaluation with data recording and analysis of liveweight production are two effective methods to rank a herd and determine just which group are the duds.

This provides producers with greater scope to increase their selection intensity and in effect gain greater results from investment in the sires that have caused some excitement this year.

Alastair Rayner is the General Manager of Extension & Operations with Cibo Labs and principal of breeding and genetics consultancy, RaynerAg. Alastair has 28 years’ experience advising beef producers & graziers across Australia. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the General Manager of Extension & Operations with Cibo Labs and principal of breeding and genetics consultancy, RaynerAg. Alastair has 28 years’ experience advising beef producers & graziers across Australia. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au