Simon Quilty

Beef Central’s guest commentator Simon Quilty ponders how the Australian cattle industry will rebuild after drought, with an empty bank account. He estimates that $800 million to $1 billion of additional finance will be needed in the first year of the rebuilding phase….

I RECENTLY attended an agri-investment conference in Melbourne which was focused on investment opportunities in Australia’s agriculture sector.

I asked the following question to a well-respected panel of prominent business people: How does the Australian cattle industry rebuild with an empty bank account?

The response was that they thought the banks would show understanding and compassion when it came to those in most need to re-finance.

In reality, this is unlikely to occur and banks are the first to admit this. I believe that when the rebuild of Australia’s cattle herd and sheep flock begins in earnest, that there will be a deficit of close to $1 billion per year for the following three years and the role of the banking sector to underwrite this need will not be there, as we have known it in the past.

The banking royal commission has changed everything

The Banking Royal Commission, I believe, has changed this lending landscape, whereby banks’ lending practices are now far more conservative than they once were. In short, it is now more difficult to get a loan if you do not have a strong balance sheet.

Anecdotally I have heard of many applications that prior to the Royal Commission took two weeks to process. Those same applications today are taking eight weeks, with no guarantee of approval. In fact in some regions, I have heard up to 50pc of new loans have been turned down or been significantly reduced in terms of available finance.

Historically, prior to the banking royal commission a large proportion of farm debt has been on interest-only terms. Under new policy from Royal Commission cases, farmers must prove ability to repay debt over a 25 year period.

This is pushing many farmers out of the market in terms of re-stocking or purchasing more land. With the land prices where they have gone, we are seeing an ever-increasing issue around how farmers continue to expand to create economies of scale when proof of serviceability just isn’t there.

One of the key recommendations of the commission was for the government to create a national farm-debt-mediation scheme that will assist borrowers to address financial difficulties that have caused loans to become distressed. In effect this will ensure mediation occurs soon after a loan becomes distressed and avoid what in the past saw mediation occurring as a final measure when lenders would take enforcement action. In other words, mediation should occur long before it’s all too little and therefore all too late to remedy the problem.

The issue is that no bank wants to have any clients fall under the farm-debt-mediation scheme and for a repeat of the horror stories that were told during the commission. So the obvious path is only taking on new clients who have a good to strong balance sheet so as to minimise any future bad loans.

As a rule of thumb, once upon a time banks would lend based 60-70pc of the asset value of a property, but since the royal commission, this ratio has fallen to 50-60pc. This dropping of the lending ratio may not apply to all banks, but it is public knowledge post the commission in rural Australia that the steps to now obtain loans have become much more difficult.

As a back-of-the-envelope calculation, if I was to use the 10pc difference as a guide to the industry-wide change in lending practices and using the guesstimate of at least trying to retain one million head of females per year (after liquidating the entire herd of close to 3.1 million head in 2.5 years) this would imply $800 million to $1 billion of additional finance needed for rebuilding and in the first year of the rebuilding phase.

As I am expecting a 60pc increase in breeding stock values after the drought breaks, this lending requirement figure could balloon out to $1.3 to $1.6 billion per year.

Looking at lending against asset value, only then a 10pc fall in available lending would equate to $130-$160 million the banks are no longer the safety for – the question is who will meet this shortfall?

In reality, using asset valuation is not the main criteria that banks used, the most important measurement is the ability of a client to service a loan and the strength of the balance sheet, and as a result the shortcoming in bank lending is likely to be even greater due to the current state of many drought-affected balance sheets.

It should be noted this does not account for the enormous amount of infrastructure spending that is required as farmers need to look to upgrade pastures, add fertiliser, improve fencing and yards and do the things on-farm that have been neglected for two years as they have put all their money and energy into maintaining livestock numbers.

Getting the three C’s right could be a challenge

As a guide for lending, banks often refer to the three ‘C’s’ – Character, Capacity to pay and Collateral. Many banks would argue that collateral is the least important of these three requirements and that the capacity to pay debt is the most important.

The problem is that in severe drought stricken regions even the best producers have a balance sheet that looks terrible this year.

If you look at a typical 450-head property in the New England region this year, it has most likely been hand-feeding for 12 months, having spent close to $300,000 on feed. Somehow, they may have maintained their core breeding herd and at best turned off 150 head at possibly $600 per head.

Before factoring any other costs they are already $210,000 in the red for the year, with no other income. Two years of this has seen a once very viable property struggle under the weight of expensive feed costs.

So this would test the character (perhaps the final ‘C’) of any farmer who’s recent struggle with cash flow has meant they do not meet the banks’ new stringent requirements post the Banking Royal Commission.

The potential shortfall I outlined of lending in the finance sector of $130-$160 million, based on collateral, is potentially enormously underestimated if cash flow is the truer funding measure which could realistically see a $600-$800 million livestock finance shortfall from the banking sector whereby the banks no longer will increase the size of the current facility or simply unwilling to give certain farmers a loan.

The additional need for infrastructure spending could see this lending shortfall balloon out to $1 billion or more per year. When I spoke to banks and rural counsellors of this likely shortfall amount, most agreed this was a very feasible amount.

The start of a new cattle cycle is a poisoned chalice as cattle prices rise

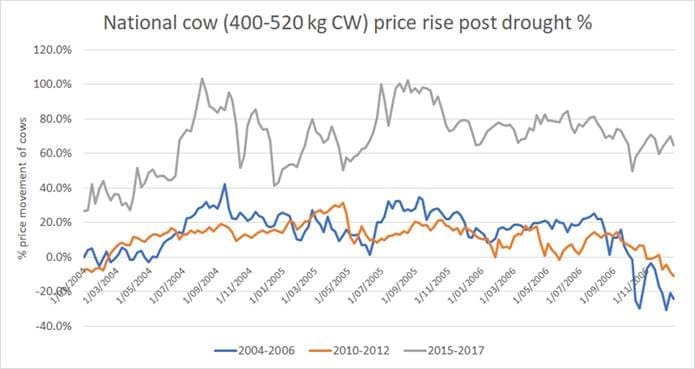

The good news is that I believe the next cattle cycle has commenced, which will eventually see cattle prices rise across Australia over the next two years. I believe the EYCI is likely to increase from today’s 532c/kg CW to 850c/kg by late 2021 – a 60pc rise (see earlier report).

The bigger challenge in the short-term is buying females, which in previous cattle cycles have seen dramatic increases in pricing in the first six months of the new cycle. This is often followed by a mild fall and then a surge with prices often peaking for a second time 12 months later. This is related to preferred joining periods in Australia’s cattle production regions, with demand for females highest during the August-November period depending on location.

The bad news is this is all well and good if a producer has feed and a sizeable cash flow to support the buying-in of breeders, but if they have no feed and conditions in their region remain bleak and a poor cash flow then they are in a helpless situation watching other regions with feed ‘buying-up’, having managed to get finance.

Regretfully those in drought-stricken areas will have to sit and wait until conditions improve in their region so they have the ability to carry animals, and by the time conditions are favourable, cattle values could be 30-50pc higher and cost prohibitive for them to buy back in.

So being the last region in Australia to have the drought break creates huge headaches as producers in that area could be trying to restock at the top of the market, from a balance sheet that is still in bad shape.

Will we ever rebuild the herd again to a level that’s sustainable?

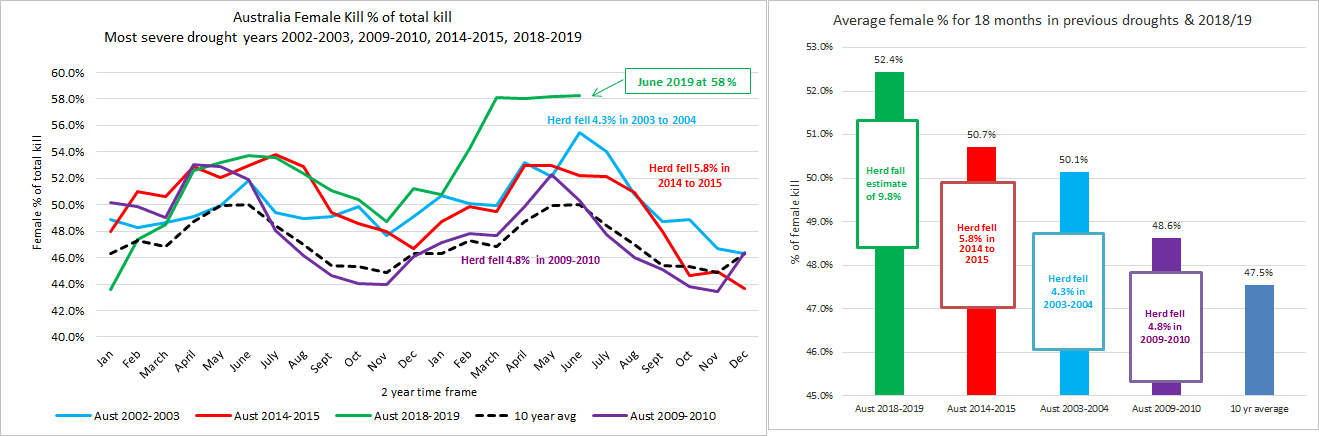

One of the concerns of industry participants is the enormous loss of the core breeding herd that has seen females being slaughtered at an unprecedented rate of 58pc for the last four months and at an average of 52.4pc over 18 months – which is far greater than any previous drought. This is likely to see a national herd size of close to 24.5 million head in 2020, I believe.

The herds in the very north of, and very south of Australia might be in reasonable shape, but they represent only a small part of the national herd. A normal big Australia drought typically has good patches where cattle are and will come from after the break, for example the Northern Territory and Queensland gulf, or Victoria, this time it seems all of Australia is dry with widespread decimation of females. So should the drought break, there are limited females to draw from for the rebuild, as those with females will hold them back and just operate normally and those with grass, but without cattle and cash will struggle to find breeders.

Other market participants I have spoken to believe the market will adjust and give the right market signals to ensure the rebuild does occur. This might see higher than expected prices for females and a much greater herd rebuild period than we have seen before.

Banks versus livestock lenders – is this the solution?

In the last two to three years we have seen new livestock lenders enter the market who are focused on financing livestock only. In other industries, this is known as inventory financing, and has been around for many years.

These lenders finance cattle and sheep only and do not finance infrastructure. The method of evaluation is similar to that of banks, which look at your balance sheet, management skills, asset value and your track record. How they do differ is that they require a very transparent approach to lending, in which they will do regular visits to inspect livestock and will be wanting to be kept abreast of livestock sales and purchases made during the life of the loan.

So the question is – are livestock lenders in competition to the banks? I think many banks might say yes to this, but I believe in reality both banks and inventory financiers can co-exist in the same industry and on the same farm.

The sharing of finance risk between different lenders is part of this, and to me this has real relevance as farmers who have traditionally run a good business but have found themselves in unfamiliar territory with a poor balance sheet may need both – the bank to help update their infrastructure that has been neglected for two years, and the livestock lender to help finance the cattle or sheep that they have bought in to restock.

The role of both the bank and the livestock lender I see evolving well beyond the drought to help grow farming businesses as the farmer starts to rebuild and with time hopefully expand.

Specialised livestock lenders

I think one of the key findings of the Banking Royal Commission was the need to have experienced agri-bankers dealing with distressed agricultural loans. But in all fairness, I think this is important for all loans, whether distressed or not.

The recent introduction of specialised livestock financing services who know the livestock sector inside out I think goes a long way to answering this need, and lifts the bar of the industry standard a little higher. I also believe many banks have good people on the ground and it’s the ongoing attention to detail that’s important as drought stricken properties get back on their feet. If experts in livestock are managing loans, I think everyone is better off.

Government involvement

Federal and state governments also play a crucial role in lending to assist farmers. Each state’s lending programs vary, so I have focused on NSW as an example of what is available.

Currently in NSW three different drought assistance packages exist (each state has its own variations) – in brief these are:

NSW Drought Assistance Fund – This provides up to $50,000 interest free loans to primary producers and is the most popular of the three loans and easily obtained. Its aim is to try and ensure a sustainable farm business by ‘drought proofing’ the property. This loan is used for installing on-farm fodder and water infrastructure, genetic banking of breeding herds and to cover transport costs of stock, fodder and water. Its purpose is to promote activities which promote profitability and resilience as a result of the on-farm investment. This loan has been popular and the most acquired to date in rural NSW.

NSW Farm Innovation Fund – This provides up to $1 million per project, so one farm is able to have several projects on the proviso that there cannot be more than $1 million outstanding at any one time to build infrastructure – this can include stock containment areas. There are no interest charges for this current financial year. This loan can be used for improved farm productivity such as building fodder and grain storage facilities, sheds, fencing, roadworks and solar power conversions; helping to manage adverse seasons such as building new dams; Improving long term sustainability through improved pastures and soil health, flood proofing properties and weed eradication. So far $394 million has been allocated, part of $1 billion in available funds.

Federal Government – Regional Investment Loan – This provides up to $2 million in loans and is over a 10 year period, with a 3.11pc variable rate with the first 5 years at interest only and then principal and interest for balance of the 10 years term. The borrower after 10 years is required to refinance the balance with a commercial lender. This loan does allow farmers to use these funds to restock and buy fodder.

One of the concerns is how well-known these government assistance packages are. In many regions of NSW, there have been workshops for farmers to make available these funds to help them get back on their feet.

‘Speed dating’ potential lenders to build a funding strategy

When talking with farmers, there is at times confusion over what funds are available to whom, and the procedures involved. There is also uncertainty over going to third parties outside of a regular bank to receive additional funds, whether it is from livestock lenders or government funding packages.

It has been suggested that one solution to try to help put some clarity on the table is to have workshops that involve all three parties – banks, livestock lenders and government assistance package advisors – under the one roof, to allow farmers to get a clear understanding of what each lender’s role is, and identifying the limitations and opportunities each lender provides. I envisage that this might involve some brief one-on-one time – like ‘speed dating’ with each lender to understand how each individual farmer’s unique situation can be best handled.

To date workshops have occurred but these have often occurred with just one lender, namely rural finance counsellors on outlining drought assistance packages. Several farmers I spoke to believe a more holistic approach which involves all lenders would be very beneficial.

Conclusion

Given the rain in certain parts of southern Australia has been falling consistently and the price of cattle in recent weeks has started to climb, there is no doubt in my mind that Australia’s livestock sector has entered the next stage in the cattle price-cycle, whereby cattle prices will start to rise over the next 2-3 years.

What is also very evident is that the cattle herds and sheep flocks have been decimated, which has seen females being liquidated at an unprecedented rate. With such a large loss there will be enormous pressure to rebuild and with that, genuine costs.

A ‘perfect storm’ in lending has occurred in Australia due to the Banking Royal Commission and drought-inflicted balance sheet deficit, which has seen changes to the lending landscape which has seen conservative lending policies by banks everywhere. This in turn has resulted in a lending deficit I believe of close to $1 billion per year over the next three years.

Australia’s lending deficit needs to be addressed sooner than later if we as an industry are to get back on our feet and recover.

I think there is a role for banks, livestock lenders and government to work together and ensure farmers get the right funds at the right time.

Love your work on Beef Central, Simon. Your attention to detail and interest in the industry is appreciated. We need more common sense discussion pieces like this to keep everyone looking at the future opportunities of our industry so we can be proactive not reactive. There are so many factors that are out of our control but issues like this are something that the big end of town and the so called people that represent us must take seriously.

Hi Simon,

Was there not a change in equity crowd funding laws last year to enable average joe consumer investment via similar methods to GoFundMe and Apps?

Would be interesting to explore this concept.