IMPROVING the performance of a beef breeding program is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

In fact improvement, particularly using genetics, can be a balancing act for many producers.

While genetics offers the potential of permanent and cumulative changes or improvements to a herd, those changes don’t come about simply through the purchase of a new bull.

Any producer seeking to start making change within their herd firstly needs to accept that genetics are a long-term investment. Depending on the scale and urgency of improvement, producers may have to instead consider what direct changes they can make to the production environment.

In some cases, changes to management and nutritional programs can be very effective in achieving improvements. However, these improvements tend to require ongoing commitment and are less likely to be permanent in the business – meaning that without proper attention, performance can easily slip backwards.

Genetics offers the opportunity to make permanent change. And while this is an opportunity, the choice of genetics has to be carefully considered in order to make sure those changes impact the herd in a desirable way.

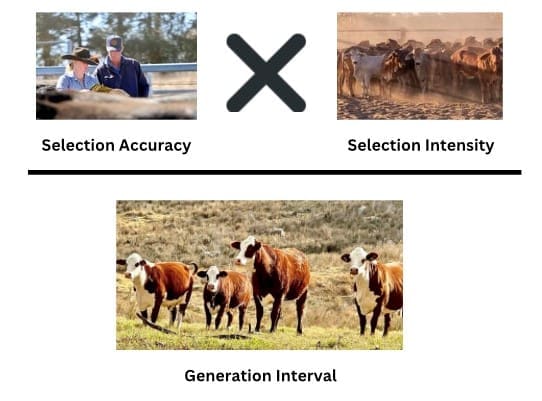

There are three key areas producers need to consider if they want to progress towards herd improvement with genetics. These factors that influence genetic gain are outlined in the image below.

The first consideration is to select sires based on their suitability to a clear breeding objective.

Sires should have published performance records. EBVs with greater accuracy can offer more certainty around the expected performance of their progeny. Using accurate information allows decisions to be made with a clearer outcome in mind, rather than a less predictable outcome using bulls with low accuracy or no EBV data.

However, using a bull with high genetic merit, confirmed through EBV and performance data may still fail to achieve expected results if he is joined to cattle of average or variable genetics.

To make rapid improvements producers should place high levels of selection pressure on their females, ideally joining the best females with their chosen sires.

Balancing expectations

While this is the ideal, for most producers there needs to be a balancing of expectations with reality. There will be occasions where the simple balance of numbers or the need to increase numbers will determine the level of intensity producers can place on females and in their choices of replacements.

It isn’t always possible to only join the best animals. In saying this, even in times where producers may have to ease their level of selection intensity in order to accommodate pressure for extra numbers, it is still increasing minimum standards for the animals that have been retained for joining.

It is possible to balance these demands by shortening joining time by one cycle, and so placing pressure on heifers to conceive earlier; culling females based on crush score at weaning and repeated at yearling age; joining only those which meet the Critical Mating Weight of 65pc of the mature weight of the cow herd.

These standards can be a good place to work from, even in times when more females need to be joined. At the very least, these requirements remove the least suitable and lower genetic merit females which does help move the herd towards more positive outcomes.

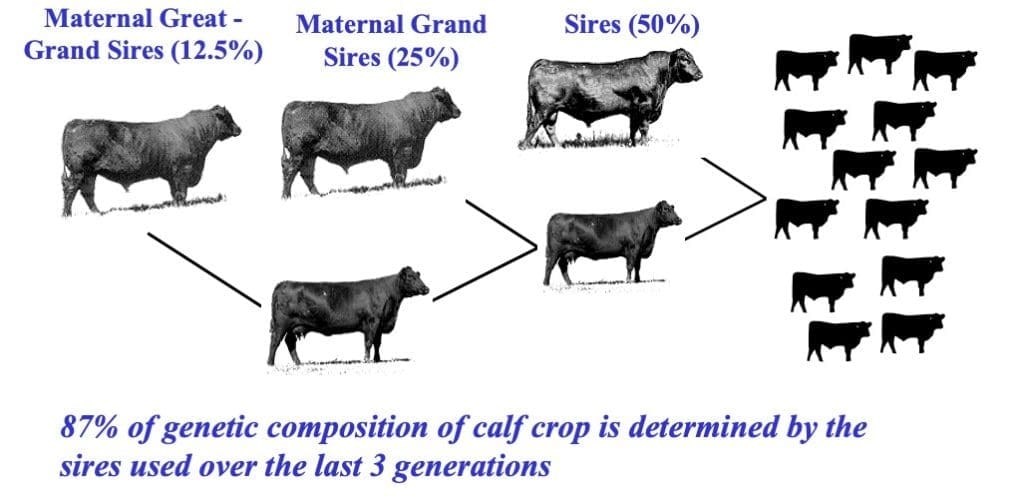

Finally it is worth considering the age structure of a herd within the context of the breeding objectives. An often overlooked fact is that 87pc of the current group of calves have their genetic composition determined by the previous three generations of sires.

This means that in herds where the age structure is skewed in favour of older cows, the opportunity for new sires to make improvements is limited by the genetic potential of the cow herd. If a cow herd has a pedigree of lower performance and is dominated by these genes, progress will be slow.

Moving the age structure towards younger females, along with using higher genetic merit bulls will increase those genes across the herd and lead to an increased rate of improvement.

Again, while this may be ideal, not all producers will want to drastically alter their cow herd age, particularly if there are age cohorts that meet other production goals. The challenge is to weigh-up whether increased genetic gain through reducing the generation interval exceeds the current level of production or offers other opportunities without increasing the risk that production may be compromised.

As producers purchase new sires and start to think about herd improvement this spring, it’s essential not to overlook the importance of focusing on how to best make the most of this investment. If genetic improvement is the key driver, then it can’t be done without consideration of selection intensity and age of the cow herd. Ultimately the rate of genetic gain has to be considered against the other factors that drive profit with beef businesses and then balanced accordingly.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

HAVE YOUR SAY