THE cost of producing a calf and bringing it through to weaning is a topic that draws considerable attention and discussion across the industry.

Dialogue around the cost of producing a calf will often touch on the cost of buying bulls, to addressing the working life of a bull, to the role that Artificial Insemination can play in commercial beef systems.

There is no doubt that Artificial Insemination (the original ‘AI’) technology has developed significantly over recent decades. The result of these developments does also mean that producers may need to shift their understanding of what AI is, and how it may be applicable to their program based on current practice, rather than ideas formed some years ago.

There is no doubt that Artificial Insemination (the original ‘AI’) technology has developed significantly over recent decades. The result of these developments does also mean that producers may need to shift their understanding of what AI is, and how it may be applicable to their program based on current practice, rather than ideas formed some years ago.

Traditionally AI relied upon heat detection, where the cow is in ‘standing heat’ or is in oestrus. Ovulation on average occurs 26 to 30 hours after the onset of standing heat. To get the best result, the aim is to have the female inseminated 0 to 16 hours prior to the time of ovulation.

Increasingly commercial producers are moving to Fixed Time AI which doesn’t require heat to be detected. Instead, an entire herd can be inseminated on the same day. This requires the producer undertaking a program to synchronise the time of ovulation of each female in the herd using a synchronisation protocol with the aim of having the majority of the herd ovulating within a 12-hour window after the time of AI.

Regardless of the breeding system used in a commercial beef herd – either AI or natural mating alone – there is a cost associated with every calf that is born and raised to weaning.

Earlier this month, regular contributor Bush Agribusiness authored an item on Beef Central considering the costs associated with the use of AI within commercial beef herds. The analysis was based on work done with five southern Queensland clients and summarised the range of costs each of the five producers recorded in their AI programs.

The analysis also considered arguments associated with the value that is often attributed to using AI to source genetically superior bulls as well as the flow-on benefits associated with shorter calving periods.

As reported, the analysis across the five herds showed a net cost associated with an AI program for beef heifers as ranging from $117 to $295/head, with an average cost of $183.

It is important to note the analysis aimed at calculating not the cost per female inseminated. The average cost of $183/head was calculated as the average cost per calf produced, concluding that, “AI may be an economical choice for some producers, however for commercial breeding businesses we’re not sure that the benefits exceed the costs in what is an expensive exercise.”

There have been some strong reactions to the original article in both the public feedback via Beef Central’s reader comments section, social media and in personal emails. Although the majority of responses have been made by individuals involved in the artificial breeding sector of the industry, there have also been responses from commercial breeders, industry extension officers and private veterinarians.

The debate regarding the cost and benefit associated with AI or natural breeding can become very heated, and it can therefore become difficult for commercial producers to actually conclude on the most effective breeding choice for their own circumstances.

It is tempting to reduce complex arguments to a common base line, often the cost of undertaking the process. However successful breeding programs are the result of a series of interlocked and complex interactions that don’t always align with a simple, cost-and-return on investment analysis.

Understanding the contributors to success – before the costs are added up

A successful Fixed Time AI (FTAI) program is the result of a number of interactions between a series of interlocking parts ranging from herd structure, management capability and environmental suitability. It is important producers objectively assess the contributors to success, and equally importantly, understand what a successful AI program actually looks like.

There are several key factors to consider, and in some case reconsider in this approach. While many people would argue that the measure of success is to produce genetically superior calves at the lowest cost, this possible undersells the additional advantages FTAI programs offer commercial herds.

It is difficult to rank in priority these advantages, however the primary driver should be seen as setting heifers up for a lifetime as productive breeders.

Many producers often choose to evaluate programs such as FTAI on the basis of cost for a program with one cohort of heifers. This evaluation, while working as a line item for an annual budget, generally fails to recognise the flow on effect within a herd that may extend upwards of seven years.

Megan Brown is the National Sales Manager for assisted reproduction company Minitube Australia. She has an extensive background in beef production and reproductive technologies, particularly in extensive areas in Northern and Central Queensland. Ms Brown suggests any evaluation of the value of FTAI within commercial beef production needs to consider the impact this has on a herd’s overall performance and breeding efficiency.

She points out that in the majority of commercial herds, either in extensively managed environments or in more closely managed systems, that although heifers “haven’t had a calf or the impacts of lactational anoestrus, the fact is, in a naturally mated system, the spread in age and weight of heifers can be as much as 6-8 months and 80-100kg different in liveweight.”

She highlights that “while producers may be able to achieve a 60pc pregnancy rate with a bull when they have their first cycle, the time in which it takes these heifers to reach that first cycle can be extremely variable, and that drift across the season leads to late calves and big variation in the calf drop and next seasons renewed rates.”

In herds where there is natural variation, due to extended joining periods, seasonal fluctuations, or other factors, FTAI can actually become a tool to reintroduce control and reset a herd. Often described as “front loading” an FTAI program can firstly achieve results in heifers which may be borderline cycling. This helps bring those females into a tighter calving period, a point that is often difficult to achieve with natural mating.

Earlier conceptions within a joining window considerably increase the productive life of a breeding female and in economic terms, increase overall profitability as those females are responsible for greater kilograms of red meat produced within their lifetime.

Ms Brown emphasises that when producers make “comparisons between Fixed Time AI natural mating using bulls alone in heifers, producers shouldn’t overlook that it is not just being used as a genetic tool. In fact, it really is a tool to set those heifers up and ultimately set the overall herd up for a tighter, more productive lifespan on the farm. The earlier a heifer calves, the more time she has to recover and re-conceive without falling out of the joining window.”

Producer Demonstration Site provides insight

One of the most recent practical demonstrations of these impacts can be seen in the MLA-funded Producer Demonstration Site (PDS) project that investigating the opportunities Fixed Time AI offered producers mating commercial beef heifers in Western Australia. Beef Central covered the project in this earlier article.

Enoch Bergman

Conducted over three years and published in 2021, the project led by Dr Enoch Bergman published data from 17 co-operating herds from a three-year period.

Dr. Bergman described the process the project undertook, saying: “In our PDS we essentially hijacked half of the heifers on a number of properties and synchronised them, after which they were AI’d. Their sisters were exposed to the bulls on the same day their sisters were AI’d, on the producers preferred mating start date.”

Ten days later the heifers were boxed, managed separately, and a number of profit driving metrics were recorded. Overall pregnancy rate was compared, along with dystocia rate, heifer loss rate, calf loss rate, weaning weights (between 100pc naturally mated vs. those AI’d and backed up by the same bulls) and rebreeding rates.

Considering the results of the project, Dr. Bergman stated: “In all parameters, the heifers randomly selected to include a round of FTAI to commence their mating outperformed the heifers naturally mated. The calves born from the heifers which had been randomly enrolled in the FTAI integrated groups consistently weaned heavier calves than those which were only naturally mated. This was likely primarily driven by the statistically significant improvement in calving date, resulting in older calves, but also by the producer’s access to bulls with superior EBV’s for 200-day weights.”

Factors affecting all breeding programs

In considering if FTAI is an investment worth undertaking in a commercial beef herd, the outcomes of this project, along with the opportunity to reset control within a breeding program are two major factors.

However, FTAI success is also dependant on factors that impact all breeding systems. FTAI does not negate the need to achieve Critical Mating Weight Targets prior to joining.

Critical Mating Weight (CMW) is defined as “The target weight that maiden heifers should reach to achieve 84pc pregnancy rate by six weeks of joining.” While Critical Mating Weight is a benchmark many producers remark upon, the actual application of this benchmark can be extremely variable across production systems.

One issue with the application of CMW benchmarks is noted by Megan Brown, as, “The problem with using a generic CMW metric in a commercial herd assessment is that many commercial herds are comprised of composites, and huge genetic and environmental variation exists that can lead to extremes in this measurement. In effect, this variation will have a dramatic impact on heifer conceptions when a generic, average Critical Mating Weight is used.”

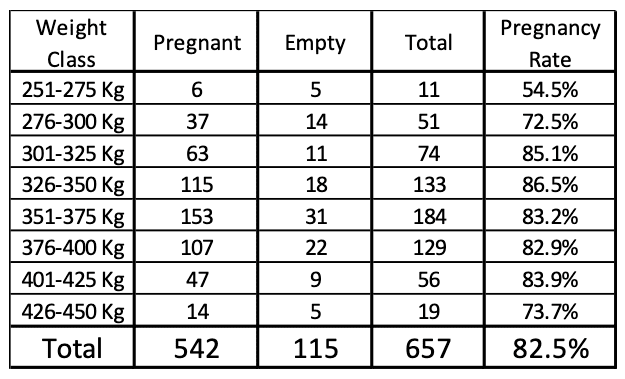

The Western Australian PDS collected significant amounts of data across the three-year span of the project.

Clearly demonstrated within this data is the importance of increasing liveweight above 300kg prior to joining. This is applicable in any breeding system, not just those planning to utilise FTAI. However, this data highlights a consideration for any producers embarking on an evaluation of the breeding system – that is, to understand what weights they are achieving for heifers prior to joining. And to reconsider if they are over reliant on a generic CMW rather than correctly measuring and knowing what best suits their herd.

Source: L.PDS.1711: Improving Heifer Productivity by Integrating FTAI into Commercial Cow Enterprises

The roll of mop-up bulls is often given a priority in FTAI evaluations. Reducing the number of bulls on hand is often a key attraction to FTAI programs. However, and often in opposition to this intent, there is an assumption held by many producers that there will be an increased requirement for “significant bull power in the mop up bulls.”

This general assumption held by many actually has little to no basis. Many producers underestimate the potential of the bulls they have on hand as well as oversimplifying the impact fixed time AI has on their heifers.

Challenging ‘fervently-held paradigms’

Well known northern industry researcher Dr Geoffry Fordyce published data on the ability of bulls to work in breeding herds and challenged the “fervently held paradigms about bull management.”

Geoff Fordyce

Dr Fordyce emphasises that northern bulls which have passed a bull breeding soundness examination (BBSE) should be capable of mating at least five times a day. He also highlights that in natural joined herds, cows may actually be mated twice or more per cycle. Therefore, it is important producers actually remember that in the first instance, the increase in numbers for a mop-up bull to serve following a fixed time AI program are not likely to exceed a fit healthy bulls’ ability to mate successfully.

Secondly, it is incorrect to assume that any heifers that didn’t successfully conceive through fixed time AI will all return to oestrus 21 days later. Research published in the US shows that return to oestrus happens over a two-week period. And in fact, only about 18pc of those heifers would be in oestrus on the same day (21 days after AI).

Additionally, there will always be a percentage of females who will experience early embryonic loss. The practical impact means there will be females on heat outside of the 21-day time frame following a fixed time AI event and that a fit healthy bull should manage to mate with these females successfully.

In evaluating FTAI these major points have to be included along with comparison of costs to produce a calf. Producers who struggle to achieve heavier weights at joining or lack the infrastructure to follow the FTAI protocols correctly are likely to experience lower levels of success. This can dramatically increase the cost per calf produced and make FTAI unappealing. Therefore, knowing what factors contribute to success is as important as knowing the financial cost.

- Next week: The final weekly Genetics Review for the Autumn 2024 cycle next week will explore this topic further.

Genetics editor Al Rayner will be on-hand as part of Beef Central’s writing team covering the Beef 2024 event in Rockhampton early next month. Catch up with him at one of the many seminar sessions covering genetics, genomics and related topics.

Genetics editor Al Rayner will be on-hand as part of Beef Central’s writing team covering the Beef 2024 event in Rockhampton early next month. Catch up with him at one of the many seminar sessions covering genetics, genomics and related topics.

HAVE YOUR SAY